Disillusioned taxi drivers are Singapore's iridium layer

Our first true scar from meteoric global impact.

DISCLAIMER: THIS IS A SUBSTACK-EXCLUSIVE ARTICLE BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE WOKE SALARYMAN.

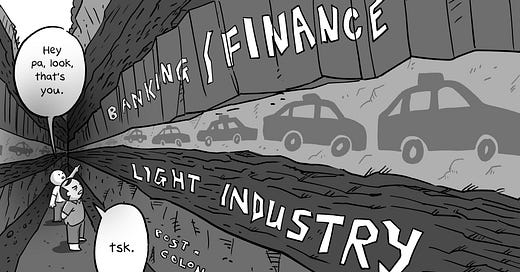

In geology, there’s something called the iridium layer — a thin, dark band of sediment found in rock formations all over the world. It marks a boundary in time. A moment when everything changed.

Roughly 66 million years ago, a meteor slammed into Earth. The impact kicked up a global dust storm, blocking out the sun, collapsing ecosystems, and triggering a mass extinction. Dinosaurs, gone. Nearly three-quarters of Earth’s species, gone.

That layer — rich in iridium, a metal rare on Earth but common in meteors — is still visible in the rock record today. A scar in the strata, fossilised in time. A clear line between the world before, and the world after.

Singapore has its own version of that.

It’s not found in rocks or fossils — it’s found in a layer of demographic, behind the wheels of taxis and private car drivers.

My own father was part of that layer.

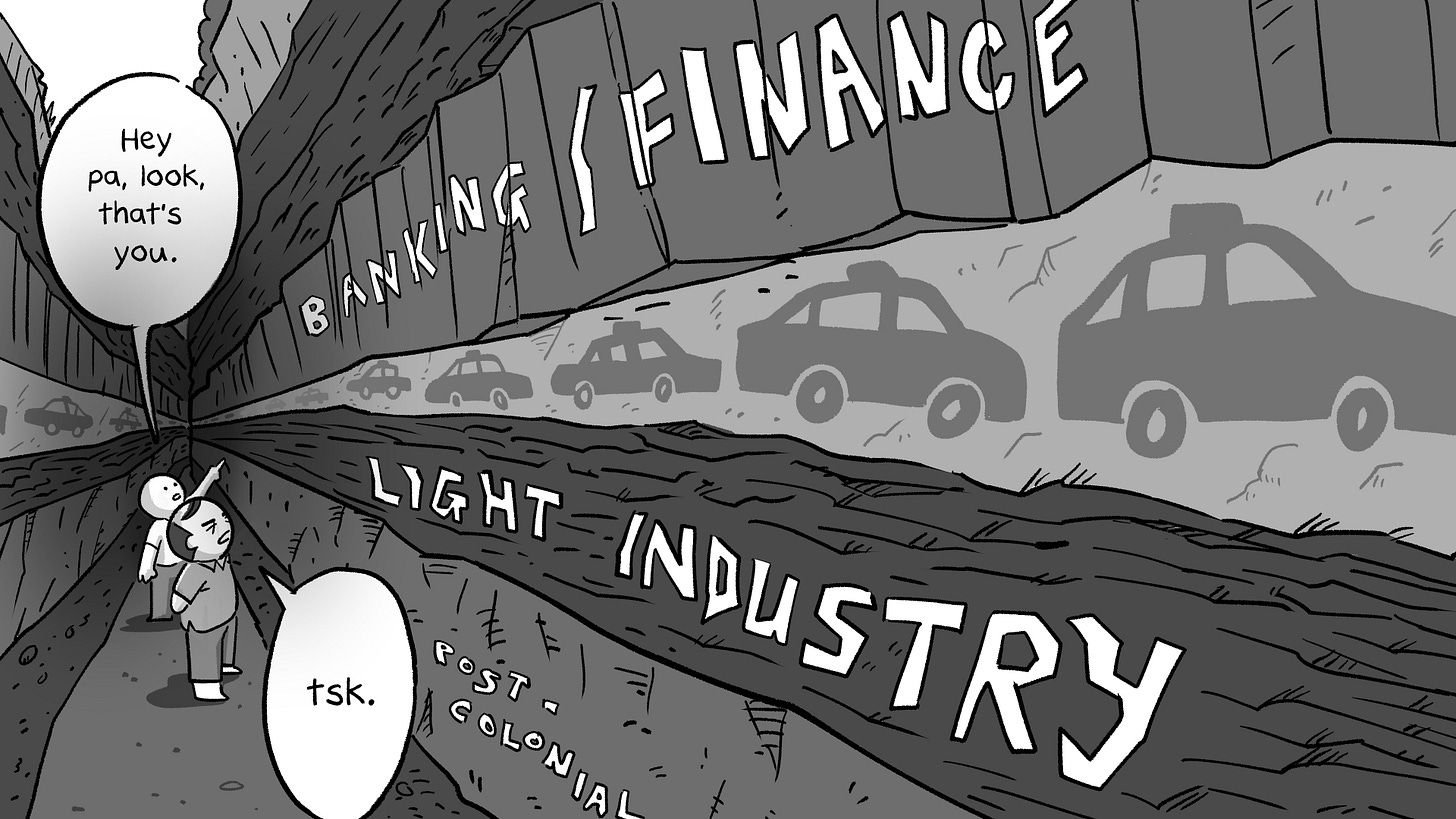

He started off as a technician in the 80s, then became an engineer by the 90s. But in the 2000s, when jobs started drying up, he looked overseas — first to a tea factory in Indonesia, then a bubble wrap plant in Myanmar. Eventually, he came home… and became a taxi driver.

Call a Grab or a taxi in Singapore and behind the wheel, you’ll often find a man in his 50s or 60s. Former engineer. Ex-IT guy. Once part of Singapore’s skilled, upwardly mobile workforce.

Now ferrying passengers through a city he helped build — but no longer feels at home in.

He’ll tell you — sometimes with resignation, sometimes with fire — that Singapore betrayed him. That he was replaced, discarded, made obsolete. That everything changed sometime in the late 2000s.

And the more I hear these stories, the more I believe:

Men like him form Singapore’s iridium layer, our first scar from globalisation. When that meteor hit, we stopped being “cheap labour” to the world — and began to feel the sting of globalisation, for real.

It was from that point onward that more and more Singaporeans would eventually face the wrath of globalisation — not just in factories or ports, but in offices, tech firms, and boardrooms.

Until the 1990s, globalisation was overwhelmingly good for Singapore.

When Lee Kuan Yew first welcomed MNCs to our shores, it was a novel chess move in a post-colonial world. Many countries – wary of their former colonial masters – viewed Singapore with suspicion.

But jobs flowed from the developed world to our little island nation. Factories, call centres, electronics, tech support — it was Singapore’s golden age of foreign direct investment. Wages rose. Infrastructure improved. People upgraded from motorcycles to cars, from flats to condos.

Along with the three other Asian Tigers (Taiwan, South Korea, and Hong Kong), we were the global economy’s ideal worker bees: efficient, English-speaking, relatively affordable, and obedient.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: Our rise came at someone else’s expense.

While we were getting ahead, workers in the US, Japan, and Europe were getting left behind. Factories shut down in Detroit. Engineers in Tokyo watched their wages stagnate. Entire towns fell into decline — as capital chased efficiency, and efficiency led it here.

For a long time, we were the cheaper alternative. We were the global disruptors. We didn’t complain, because it worked — for us. Social studies textbooks (circa 2005) sang mostly praises about globalisation.

But by the mid-2000s, the cycle turned. It had been a long time coming. China opened its economy in 1978. And other neighbours who had observed LKY’s methods work so well decided to get on the bandwagon.

We got expensive. And we were no longer “value for money”.

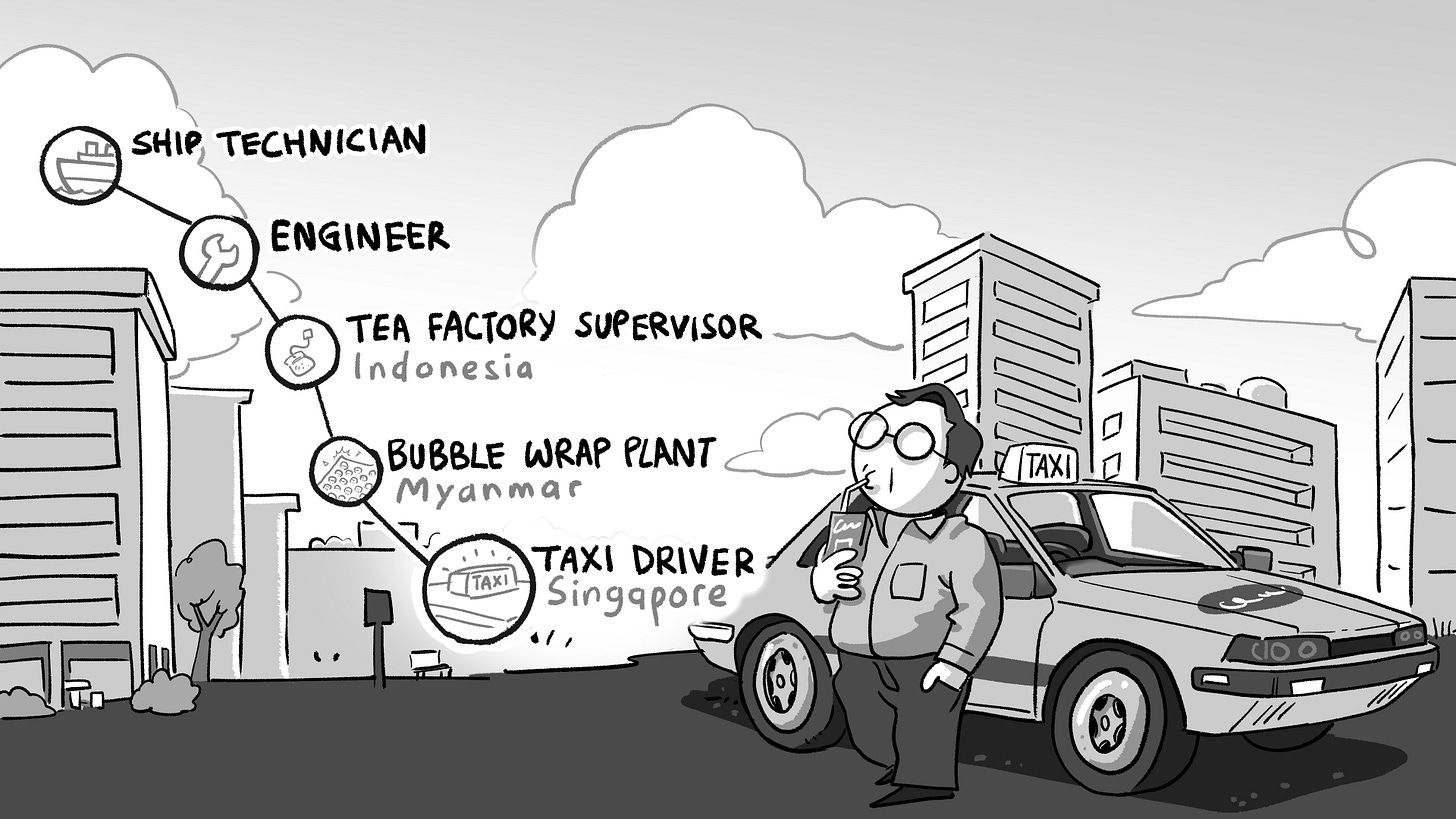

Low-end manufacturing flowed out of Singapore. Factories started shuttering. And eventually, developing countries produced talent on par with Singaporeans. Yet several times cheaper.

Singapore still wanted growth, so instead of letting everything flow out, we opened the floodgates to foreign PMETs, especially from India, China, and the Philippines, who could work here for lower pay than local PMETs.

Competition rose. Xenophobia spiked. Elections were lost.

And we finally got a taste of what other developed countries had been feeling for decades.

Singapore is not immune from the ills of globalisation, and we never were.

Many younger Singaporeans are confused by what’s happening around us.

Why they're not experiencing the same income mobility as compared with their parents.

Why the same jobs that could once raise entire families are no longer enough to buy a resale HDB in a popular neighbourhood.

Why their dream of guaranteed employment at some MNC gig that pays five digits is increasingly out of reach.

Why increasingly, knowledge of overseas markets is becoming more and more important.

Well, the answer is simple.

We rode the first wave of globalisation to all its glory. But now that wave has passed us, and we’re grappling with what it really means to be a developed country, with developed country problems.

The problems we face — whether it's the shrinking middle class, income inequality, or stagnating wages — have all been faced by others before (and at a far larger scale).

Never make the mistake of thinking we’re so exceptional that we’re exempt from them.

And if you ever need a reminder about how it might impact you negatively, don’t worry.

I’m sure you’ll hear all about it.

Perhaps here, but also perhaps in the backseat of a taxi.

Stay woke, salaryman.

If you’ve read this far, please consider subscribing to our email newsletter (yes, this Substack). We cannot offer you much but we can offer this:

We have newsletter-exclusive articles that won’t be posted anywhere else. We created these articles for people who want to go deeper into complex issues than the shorter-form content we typically have.

If you don’t have social media or don’t follow our Telegram channel, you can still get updates to all our content emailed directly to your inbox to read at your own time.

We promise not to spam your inbox (but Substack might, so update your notification settings).

With a name like "Toh Soon Industries", maybe it wasn't just globalisation 😂

well written which truly reflects what is happening around us in this society. Globalisation is a double edge sword, once oversaturated, the consequence will be reversed.