The unexpected ways ageing populations can affect the young

Yes, it has implications on politics too.

Not discussed in human geography textbooks. At least when I was still in school.

When I was in Secondary 3 all the way back in 2005, I took geography as one of my electives. Like many of my peers, I memorised chapter after chapter of my old textbook.

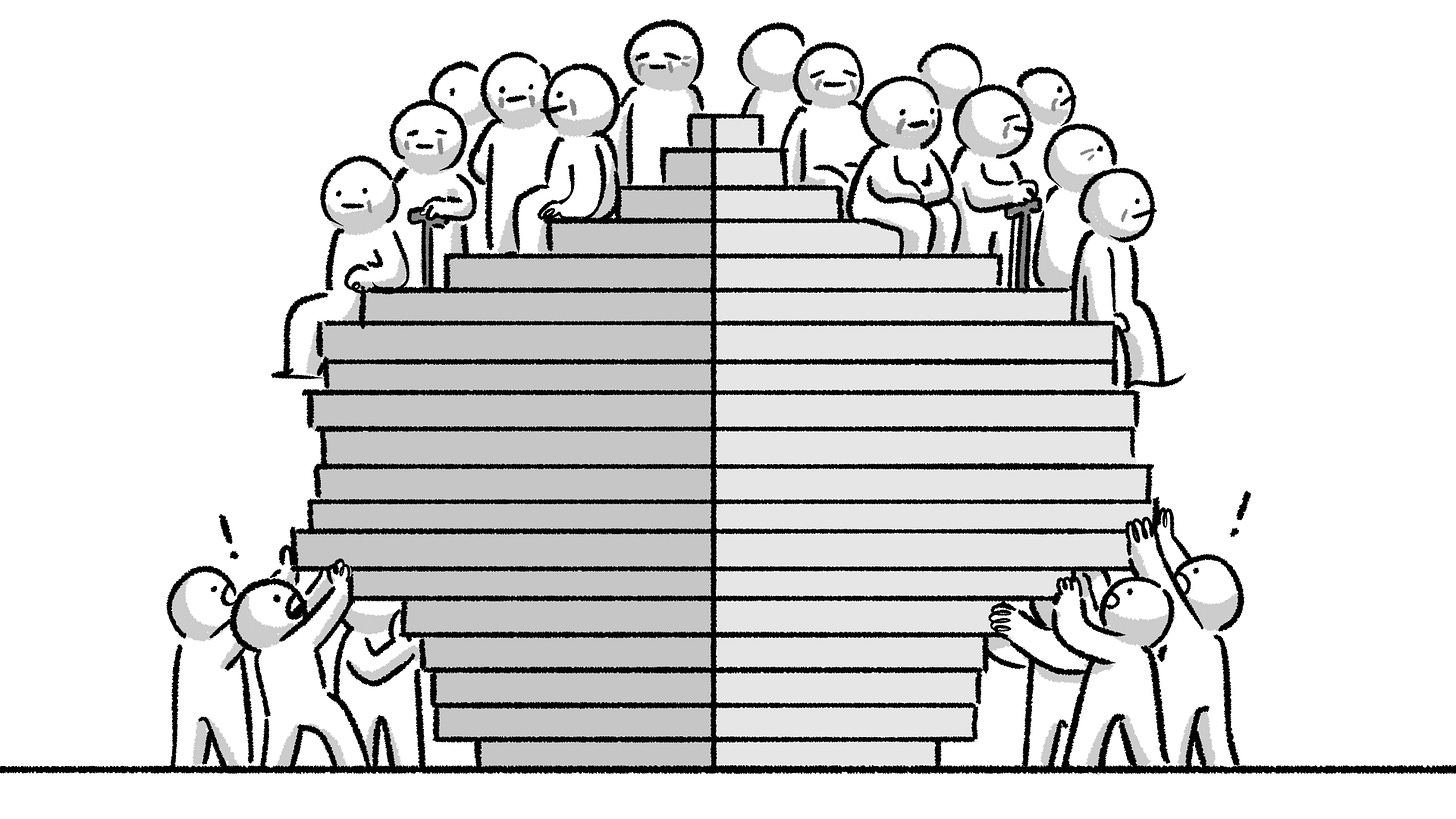

On one of those pages were the classic population pyramids.

And of course, the phenomenon of an ageing population. The main points to remember about that particular concept was the idea of the dependency ratio.

“The more older people there are, the greater the burden on the working population who have to pay more taxes to support them.”

That line was burned into my brain, so I could regurgitate it during exams. Yes, the classic rote learning.

As a 15-year-old, I never really fully processed what I was learning. But as it turns out, two decades later, the ageing population timebomb that we studied about is finally here.

Some of the effects of the ageing population are obvious, familiar, and well-repeated.

Increasingly, Singapore spends more of its budget on healthcare on its growing proportion of elderly. In 2010, Singapore’s healthcare spending was S$11.3 billion, versus the $21 billion set aside for 2025. By 2030, it’s estimated that it will exceed S$30 billion.

That’s now the largest social expenditure, even surpassing education.

Singapore’s workforce growth has slowed significantly in recent years, driven by a rapidly ageing population and fewer young entrants. To counteract these trends, we’ve relied on foreigners to plug the gap – which in turn tests social cohesion.

Parents are stressed, because they’re trapped between child-rearing and caregiving. Others are not having children because they fear being trapped in the sandwich generation.

You already know all of this.

But there are other problems that are caused by an ageing population. Some have already happened in Singapore.

As Singapore approaches a ‘super-aged’* population in 2026, it’s important to give these potential issues some attention.

*According to the UN, a super-aged society is when more than 21% of the population are aged 65 and above.

The risk of a silver democracy

As people live longer, they also get to vote longer.

That’s a problem, because in democracies, a vote carries the same weight regardless of age. If a country has a large proportion of elderly, they’ll be able to influence policies for an extended amount of time.

By itself, this isn’t an issue. However, there’s a real risk that elderly populations vote for policies that are entirely in their interest. This is known as the ‘gerontocracy problem’.

In the many developed countries around the world, this is precisely what has happened:

In Japan, pension policies are politically untouchable due to elderly voter influence.

In the UK, Brexit had disproportionately high support from older voters, despite younger generations largely opposing it.

Now, I don’t think we have anything as drastic as this in Singapore. We have a single party government, and no parties that exclusively serve the needs of the elderly. And I’d like to think that most elderly Singaporeans care about the next generation (I could be wrong).

However, we can still see some element of it in the resale HDB market:

With HDB prices becoming out of reach for young people, a seemingly straightforward approach would be to cap resale prices.

However, this would affect the net worth of elderly Singaporeans (majority homeowners) who have their net worth put in their HDB flat; many of whom depend on the value of their flats for retirement, or want to pass down inheritance.

Putting limiters on price would hence be an unpopular move with big implications.

Housing issues

In many countries around the world, the young are pushed to the fringes of the city, as they can’t afford the properties in central areas. The average New Yorker can only dream of affording property in Brooklyn or Manhattan.

Elsewhere, young professionals are pushed out to ‘commuter cities’ like Luton or Reading, and make trips into London for work.

In the same way, younger Singaporeans might live in Bukit Panjang, or say, Sengkang, instead of pricier, more established neighbourhoods: Bishan, Queenstown, Ang Mo Kio.

This happens for a variety of reasons.

Older generations have had decades of accumulating wealth, so they’re going to be able to outbid younger generations who don’t have a similar runway. Many of them are also current homeowners who have already benefited from price appreciation.

They have plenty of options. They can sell their current home to finance another. Hold out for a buyer that meets their expectations. Or simply not sell. Which brings us to our next point:

Like it or not, people living longer directly affects the housing supply.

When life expectancy was shorter, older folks would pass on (or at least move in with their children or to a care facility), and reduce demand in the housing market. But with people living for 5, 10 years longer — things have changed.

So yes, the retiree who continues to live in their 5-room HDB flat long after their children have left the nest is fully entitled to do so (a.k.a. ageing in place).

But that’s one less spacious flat for millennial (or Gen Z) parents who want to have more children.

Crowded corporate ladders

‘I can’t get promoted unless my boss leaves’ – one too many people

The longer people live, the longer they work.

Let’s just say upfront that this isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

We are also well aware there is a certain negative bias against some segments of older workers. Our stance is that ability should be considered first and foremost, not age.

If older folks can continue working in their old age, they’ll be able to pay taxes and pay for themselves, reducing financial burdens on the younger generations.

But this is also a double-edged sword.

I don’t have the empirical data; but it's becoming a common trope when I meet my friends; they have to wait for their bosses to leave, or retire before they can get promoted.

This is a real problem in many organisations where promotions are tied to seniority instead of competence. This applies to managers, directors, even boards of directors. If leadership roles are occupied indefinitely, it’s only natural that younger workers feel like they’re wasting their time waiting for someone to retire.

At some point, companies (or organisations) will have to rethink career progression, or risk losing talent that refuse to wait in line.

Further reading: The uncomfortable truth about crowded corporate ladders

All of these contribute to a disillusioned youth

The 2020s have been tough for millennials around the world.

We didn’t experience the same wage growth our parents did. Society is becoming more unequal, and traditional paths of success that our parents followed (or forced us on) haven’t quite lived up to expectations.

We went through an economic crisis, and then a pandemic.

At best, we’re delaying traditional milestones like marriage, homeownership and raising children. At worst, we’re giving up entirely on work and love. We’re doomsday spending. Hiding away from societies in our parents’ homes.

This is further exacerbated by our older parents/relatives/colleagues who don’t always fully understand the challenges or realities that we face. And it’s frustrating that they might be contributing to it.

But generational warfare is not the way to go

As tempting as it is, I don’t think it makes sense to completely blame the previous generations for ruining our lives. And thankfully, the idea of ‘generational warfare’ hasn’t taken off in Singapore that same way it has in the US.

Put in the same position, it’s not difficult to imagine millennials, say, voting for policies aligned with their welfare. Or wanting to work longer because they’re lacking retirement funds.

Intent also counts: It’s hard to imagine an entire generation of people planning how to ruin their offsprings’ lives, as far as 50 years ago. Hindsight is always 20/20. Older folks didn’t certainly know how long they would live to, and the ripple effects they would cause.

Last of all, how we treat our elderly says a lot about how we are as a society. Like it or not, older generations in Singapore have contributed to the nation; it's not morally right to discard and alienate them just because we think their prime days are over.

That said, youth are the future of the nation.

What would Singapore be if its young people get tired of trying?

These are hard questions we have to confront together.

Hopefully peacefully at the dinner table.

Stay woke, salaryman.

If you’ve read this far, please consider subscribing to our email newsletter (yes, this Substack). We cannot offer you much but we can offer this:

We have newsletter-exclusive articles that won’t be posted anywhere else. We created these articles for people who want to go deeper into complex issues than the shorter-form content we typically have.

If you don’t have social media or don’t follow our Telegram channel, you can still get updates to all our content emailed directly to your inbox to read at your own time.

We promise not to spam your inbox (but Substack might, so update your notification settings).

Having a price ceiling on resale prices is hardly a straight forward proposition and I don’t think it should be blamed on a voter bloc…. You guys normally have a good grasp of economics so you should know the economic difficulty of enacting it… For example, if 4-5 people fancy a property and they cannot outbid each other via the price mechanism because of a price ceiling then how does the seller or HDB allocate the property? Ballot again?

Wow, a lot of information to process ...